Facial mimicry and social cognition in children with autism spectrum disorder

When we want to understand each other better, we tend to copy one another's facial expressions. How does this work in children with autism spectrum disorder? In this blog post, you’ll learn more about facial mimicry in ASD.

Posted by

Published on

Tue 14 Nov. 2023

Topics

| Action Units | Autism | Developmental Psychology | Emotions | FaceReader | Facial Expression Analysis | Developmental Disorder |

When we want to understand each other during social interactions, we tend to copy one another's facial expressions. This facial mimicry not only helps along the conversation but is also associated with better emotional understanding and empathy1. So, what happens when facial mimicry is impaired?

In this blog post, we discuss the work of researchers Liu, Wang, and Song as they study the underlying processes of facial mimicry in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD)2.

Facial mimicry in ASD

When studying facial mimicry in people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), researchers have found mixed results. Many developmental psychology studies show deficits in facial mimicry, while other researchers find that this skill is intact in people with ASD. It is also unclear whether problems with facial mimicry are core deficits in ASD and what their relationship is with social cognition.

To shed more light on this subject, Liu's team examined the underlying processes of facial mimicry in this group. This includes Theory of Mind (ToM) and executive functioning (EF), both important functions in understanding social cognition. Moreover, they distinguished between two types of facial mimicry: automatic and voluntary.

Want to read more about research on autism spectrum disorders? Check out this free white paper.

Different aspects of facial mimicry

Automatic facial mimicry is fast, spontaneous, and unconscious. It just happens, you don’t have to think about. On the other hand, you have voluntary facial mimicry. This is when you consciously focus your attention on copying another’s facial expression. It’s slower and more effortful.

So, what if people with ASD don’t have an overall deficit in facial mimicry, but only for specific types? Based on earlier research on this subject3, the research team hypothesized that people with autism spectrum disorders may only have an impairment in automatic facial mimicry, and not the voluntary type. Moreover, facial mimicry in ASD may vary across different emotions4. In other words, individuals with ASD may copy facial expressions in an atypical way, instead of not being able to.

How to measure facial mimicry

What’s the best way to study automatic and voluntary facial mimicry of different emotions? Some studies have employed electromyography (EMG) to examine the activity of a specific facial muscle that’s a clear marker for an emotion, such as happiness or anger. However, this type of study has its limitations, as it’s too difficult to study entire facial expressions or for researchers to observe muscle activity for themselves.

That’s why the research team from the current study chose a different approach. Using FaceReader, they gained a classification of six basic emotions, as well as a quantitative measurement of facial action units. With this type of facial expression analysis, they were able to study facial mimicry in entire facial expressions.

FREE WHITE PAPER: FaceReader methodology

Download the free FaceReader methodology note to learn more about facial expression analysis theory.

- How FaceReader works

- More about the calibration

- Insight in quality of analysis & output

Facial mimicry, Theory of Mind, and executive functioning

The research team also examined how ToM and EF relate to facial mimicry in ASD. Theory of Mind refers to the ability to understand the mental states of other people, which is essential for social cognition. Executive functioning is a set of higher-order cognitive processes we need to plan our next move or inhibit our behavior. As such, EF is also a necessary skill for controlling imitation behavior. As the researchers from this study point out, it is worth investigating whether ToM or EF mediates the mechanisms of facial mimicry in children with autism spectrum disorders.

Facial expression analysis with FaceReader

The team included 21 children with ASD in their study, as well as 22 typically developing children that were matched in age and IQ. To measure facial mimicry, all participants watched images of facial expressions for 6 basic emotions (happiness, sadness, fear, surprise, anger, and disgust).

At first, the children were simply told that they would watch facial expressions. This way, the researchers could observe automatic facial mimicry. Next, they asked participants to watch and simultaneously copy the facial expressions they saw on the screen, as a measure of voluntary facial mimicry.

During this task, children’s facial expressions were recorded using FaceReader. The team used these recordings to measure how accurately they copied facial expressions and with which intensity.

MEASURE YOUR EMOTIONS: What does your face say?

Curious what emotions your face shows? Upload a photo here, and our FaceReader software will test it for emotionality.

- Enter a url or browse for an image

- Use passport photo like pictures

- Make sure that the pictures you upload are the best they can be

Lower intensity of facial mimicry

In both groups, children’s facial mimicry was more accurate in the voluntary condition compared to the automatic copying of facial expressions. Interestingly, there were no differences in accuracy between the groups. However, the research team found that children with ASD show lower facial mimicry intensity than their typically developing peers, for emotions happiness, sadness, and fear.

Moreover, they found that both automatic and voluntary facial mimicry were correlated with Theory of Mind (ToM), and not executive functioning (EF). As reduced facial mimicry is also associated with greater social dysfunction5, these results support the idea that ToM mediates the relationship between ASD symptoms and intensity of facial mimicry.

Facial mimicry as a potential marker for autism

So, what does this mean for helping children with ASD? As the researchers suggest, atypical facial mimicry may be an additional marker to help refine the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. In other words, studying how children copy facial expressions may help to figure out more about their symptom severity, particularly regarding social dysfunction.

To use this information more reliably in clinical settings, the research team suggests that future research should focus on bigger and more varied samples of participants, as well as more dynamic facial expressions. This way, we’d get a better look at how children with ASD perform on facial mimicry in everyday life.

References

- Holland, A.; O’Connell, G.; Dziobek, I. (2021). Facial mimicry, empathy, and emotion recognition: A meta-analysis of correlations. Cognition and Emotion, 35(1), 150-168. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2020.1815655

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y., Song, Y. (2023). Atypical facial mimicry for basic emotions in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 16, 1375-1388.

- McIntosh, D.; Reichmann-Decker, A.; Winkielman, P.; Wilbarger, J. (2006). When the social mirror breaks: Deficits in automatic, but not voluntary, mimicry of emotional facial expressions in autism. Developmental Science, 9(3), 295-302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00492.x

- Oberman, L.; Winkielman, P.; Ramachandran, V. (2009). Slow echo: Facial EMG evidence for the delay of spontaneous, but not voluntary, emotional mimicry in children with autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Science, 12(4), 510-520. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00796.x

- Deschamps, P.; Coppes, L.; Kenemans, J.; Schutter, D.; Matthys, W. (2015). Electromyographic responses to emotional facial expressions in 6-7 year olds with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Development Disorders, 45(2), 354-362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1890-z

Related Posts

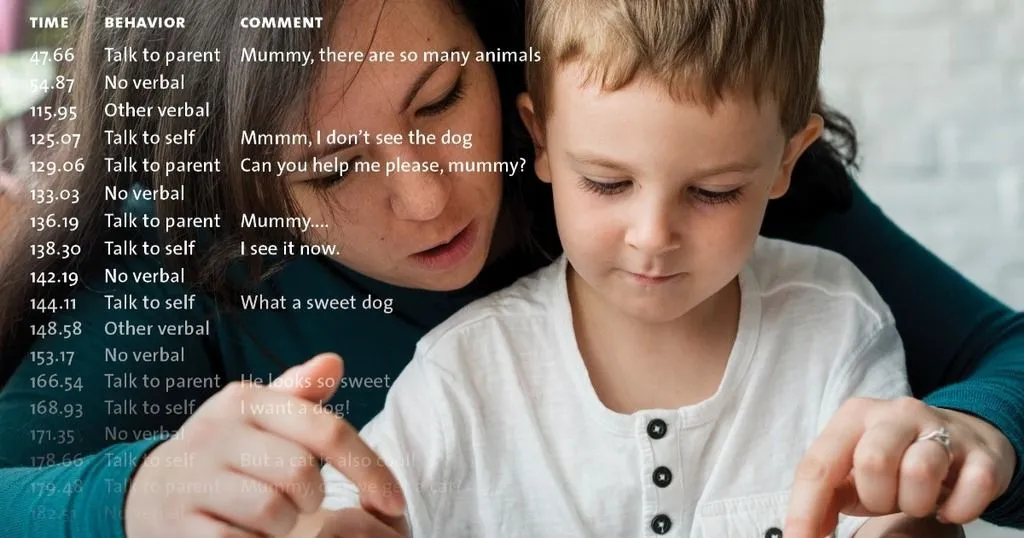

Systematic behavioral observation – two coding scales

PCIT: Parent-Child Interaction Therapy