Choosing the right parameters in CatWalk XT

CatWalk XT provides the opportunity to study a variety of gait parameters. But, which parameters should you use for your mouse model? Read this blog to learn more!

Posted by

Published on

Thu 13 Jul. 2023

Topics

| Ataxia | Gait Analysis | Methods And Techniques | Parkinson's Disease | Spinal Cord Injury | Stroke | Traumatic Brain Injury | CatWalk XT |

Every year many researchers switch from traditional paw inking to an automated system for gait analysis. Automatic gait analysis systems like Noldus’ CatWalk XT vastly improve reliability and efficiency of your research. However, making sense of the data generated with by automated methods is not always straightforward. You might be asking yourself questions like: What parameters are important for my disease model? Which parameters are important during disease progression? And perhaps many more.

In this blog we will be looking at a paper written by Ivanna Timotius together with, among others, CatWalk XT product manager Reinko Roelofs [1]. In this paper Timotius et al. performed a meta-analysis of studies that used CatWalk XT. They looked at the readouts of those studies and which parameters were significantly impacted by certain diseases models. The aim was to use this information to help users select parameters to initially focus on in their disease model.

Uncovering gait parameters

For this meta-analysis the researchers analyzed 91 peer-reviewed studies that used gait analysis in commonly studied disease models. They assessed the parameters that were reported as results in these studies and whether they significantly increased, decreased, or were not significantly different when compared to control animals. Most of these studies were published recently (between 2017 and 2022).

The researchers highlighted 6 commonly used disease models related to gait impairments, namely: Parkinson disease (PD), stroke, spinal cord injury (SCI), traumatic brain injury (TBI), severe neurological damage (SNI), and Ataxia.

What is CatWalk XT?

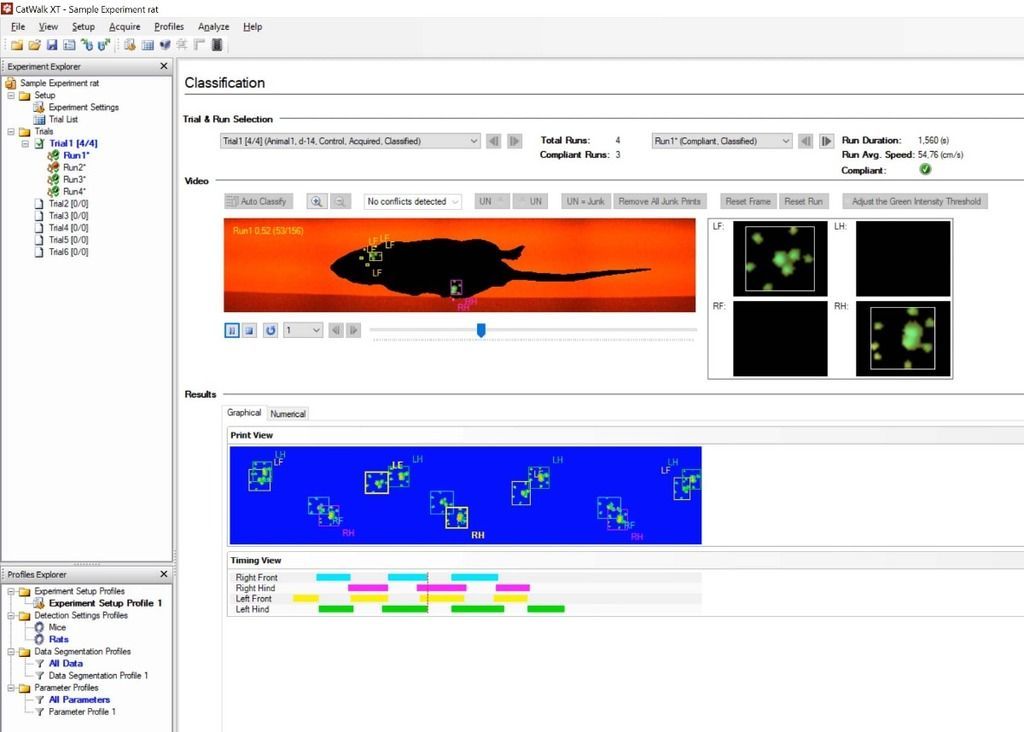

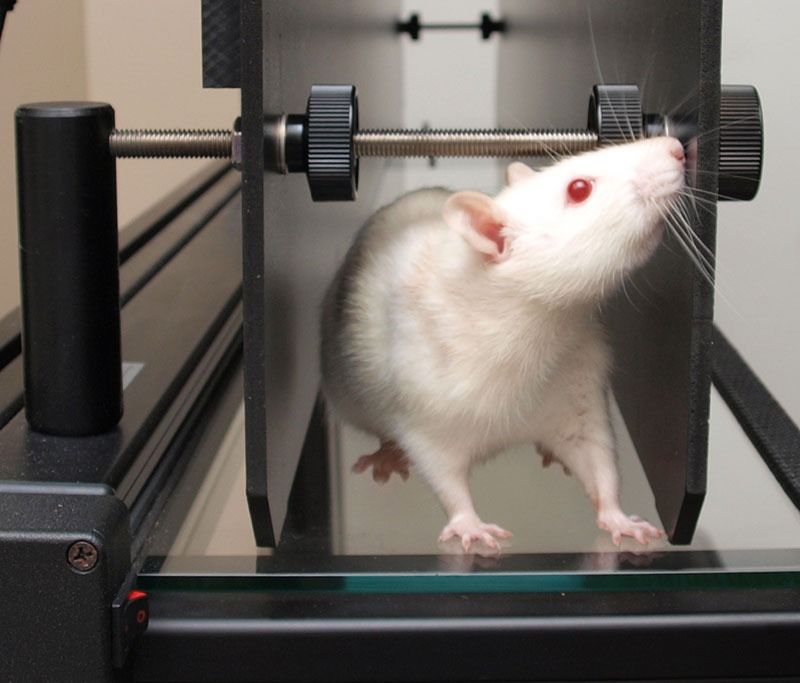

But before we continue, what is the CatWalk XT? And why is choosing the right parameters so important? CatWalk XT is the golden standard forobjectively detecting overground gait in rodents. While an animal walks across a glass walkway, its gait is recorded from below. Green LED light is internally reflected inside this glass plate except when contact is made with the plate. This way only the actual footprints scatter light and are detected by the software.

RESOURCES: Read more about CatWalk XT

Find out how CatWalk XT is used in a wide range of studies and how it can elevate your research!

- Free white papers and case studies

- Customer success stories

- Featured blog posts

Rodents in the CatWalk XT are trained to traverse voluntarily a narrow dark walkway corridor towards a goalbox. This eliminates stress and gives great insight into the walking ability of all disease or injury models.

From each traversal many different parameters can be assessed like stride length, stand time, duty cycle, print area, to name a few. Using an automated gait analysis system with a high spatial and temporal resolution allows for the detection of subtle changes in gait that cannot be observed by manual observation. However, this is where confusion might arise. Having the option to measure more than 50 parameters doesn’t mean you should consider them all in your analysis, or that they will provide any valuable insight. Therefore, knowing which parameters to use, and determining them beforehand, is essential in correctly using an automated gait analysis system.

Which parameters should I use?

So, what were Timotius et al. able to conclude? Many papers had conflicting results when analyzing the same disease models due to differences in mouse strain, injury model and laboratory practises. However, some parameter changes were more consistent. For example, PD mouse models had an increased stand time and decreased swing speed, when compared to control mice. This was also the case for SCI mice, which also had a significantly different regularity index (the exclusive use of a normal step sequence patterns during uninterrupted locomotion). Differences in stride length and changes in hind paw base of support shows that parameters related to compensatory mechanisms to restore balance are very useful for ataxia models.

Run speed, maximum contact area and swing speed were all significantly decreased in stroke mice. In SNI mice the intermediate and average toe spread was significantly decreased or increased, which could be because of the different mouse models used. Lastly, phase dispersion and the mean of max intensity were different for mice with TBI.

Interestingly, the less site specific the disease is (like stroke and TBI), the more parameters were significantly changed by the injury. This is likely because of the large and varied effect these parameters have on the brain, which causes more symptoms to develop.

Moving forward

So, how do we move forward with these conclusions? It is important for researchers to know the parameters to initially look for in their disease model as highlighted above. Furthermore, it is essential that researchers consider how certain environmental or genetic factors have an influence on gait variables such as housing, handling, disease model and many other factors.

This doesn’t mean that everything can or should be perfectly standardized. If certain results are truly robust, it will be less influenced by external factors. However, it is crucial to state that reporting on these factors is still needed for a complete understanding of why certain results might deviate from other studies.

In conclusion the study by Timotius et al. recognizes the inherent biases and limitations in their approach due to reliance on published data. They do also emphasize the need for comprehensive and detailed reporting in gait studies, which will significantly enhance the reliability and relevance of gait analysis tools such as the CatWalk XT, while in turn increasing the understanding of CNS and PNS injury models.

REQUEST INFORMATION

Do you want to learn more about gait analysis and need expert advice? Let's talk!

- Advance your research

- Get expert guidance

- Profit from our 35+ years of experience

References

1. Timotius, I.K.; Roelofs, R.F.; Richmond-Hacham, B.; Noldus, L.P.; von Hörsten, S.; Bikovski, L. CatWalk XT Gait Parameters: A Review of Reported Parameters in Pre-Clinical Studies of Multiple Central Nervous System and Peripheral Nervous System Disease Models. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1147784.

Related Posts

What a print can tell

Going the distance - and why it matters in gait analysis