How obese mice get moving

By a showing of hands: how many of you started this New Year with the resolution to get moving? Burn off those extra holiday calories, or finally really get in shape?

Posted by

Published on

Thu 26 Jan. 2017

Topics

| Behavior Recognition | EthoVision XT | Mice | Obesitas |

By a showing of hands: how many of you started this New Year with the resolution to get moving? Burn off those extra holiday calories, or finally really get in shape? Because, let’s be honest, it’s all about willpower right? “Just do it!”

It might not be that straight-forward…

We all know getting active is good for our health; it is scientific fact that obesity and physical inactivity are linked. But what comes first? Gaining weight because you don’t move enough, or decreasing activity because it’s just harder to get around with the physical burden of that extra weight?

The science behind the weight

A couple of weeks ago, I spoke to Alexxai Kravitz at Neuroscience 2016 in San Diego. His lab at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK, National Institutes of Health, US) has the goal of understanding the underlying physical behaviors related to obesity. Their work was recently published in Cell Metabolism and received quite a bit of attention in the press.

It’s in your head

The Kravitz lab asked the question: "…dopamine is critical for movement, and obesity is associated with a lack of movement. Can problems with dopamine signaling alone explain the inactivity?"

They actually found that inactivity, at least in part, was caused by problems in the dopamine system in the brain, specifically, activity of the dopamine 2 (D2) receptor.

Getting fat

One group of mice was fed a normal diet, while a second identical group was given high-fat food. Within a week, a noticeable difference in body weight appeared between the two groups. By week four, the heavier mice were also significantly slower. However, here is the interesting part: the overweight mice got slower before they gained significant weight.

What’s going on? Analysis of brain chemistry showed that the high-fat diet caused a deficit in activity at the D2 receptors in the striatum, which in turn caused the decrease in activity.

How to get lazy

So if this is true, lean mice with a defect in the D2 receptors should show the same decrease in activity, right? Indeed, they did. When researchers later restored D2 receptor activity in the heavy mice, they showed an increase in locomotor activity, despite being overweight.

Investigating behavior

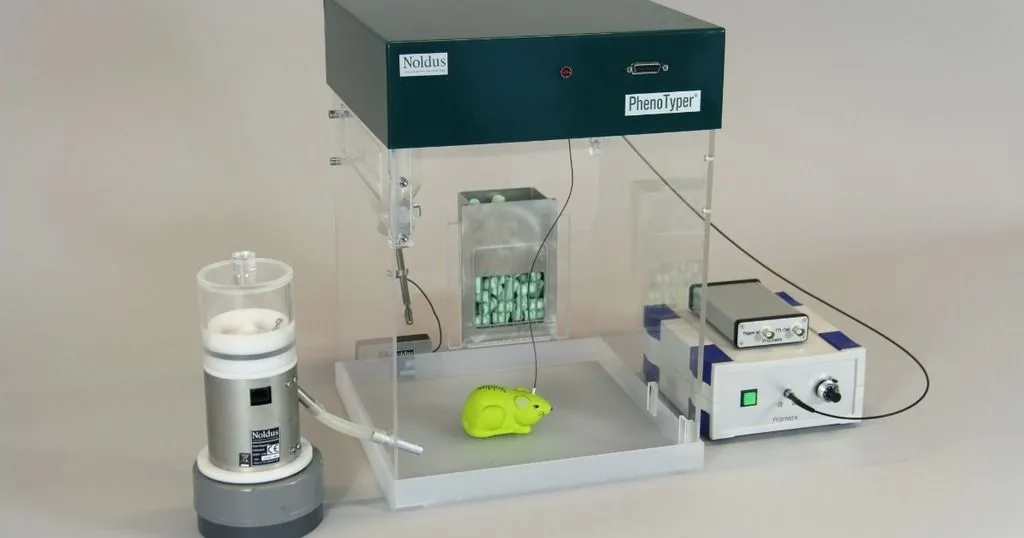

Activity was quantified in this study using automated methods, and the researchers measured activity and speed via the video tracking system EthoVision XT in open field environments (Noldus PhenoTyper chambers). EthoVision XT was also used to automatically measure grooming and rearing (via the Mouse Behavior Recognition Module).

The measurements showed that the overweight mice got ‘lazy’ by week four. Decreased movement was characterized by spending less time moving, and slower movement overall. Although they seemed to rear less, this was not a significant difference compared to the lean mice; time spent grooming also did not differ.

The bigger picture

Obesity is a leading cause of preventable death. In 2014, over 600 million people were classified as obese (World Health Organization). The health issues are obvious, as are the need for interventions. Getting active is a vital part of getting healthier, but as this study suggests, it is often not simply a case of willpower or mindset.

Insights from this study, and further research Kravitz and his team are planning to do, offers great steps towards a better understanding into the pathway underlying obesity.

Read more

- Friend, D.M.; Devarakonda, K.; O’Neal, T.J.; Skirzewski, M.; Papazoglou, I.; Kaplan, A.R.; Liow, J.-S.; Guo, J.; Rane, S.G.; Rubinstein, M.; Alvarez, V.A.; Hall, K.D.; Kravitz, A.V. (2016). Basal ganglia dysfunction contributes to physical inactivity in obesity. Cell Metabolism, 25, 1-10.

- More about EthoVision XT: www.noldus.com/ethovision

- More about PhenoTyper: www.noldus.com/phenotyper

- More about automatic behavior recognition: www.noldus.com/behavior-recognition

Related Posts

![Neuroscience conferences in 2020 [UPDATED]](https://mescalero.noldus.com/storage/core-blog/neuroscience-conferences-2020.webp)

Neuroscience conferences in 2020 [UPDATED]

Noldus on the Road: animal conferences in 2026