Robots helping people with dementia

Researcher Wendy Moyle and her team explored if the use of a robotic seal as a therapeutic tool would influence the emotional and behavioral symptoms of dementia.

Posted by

Published on

Mon 23 Oct. 2017

Topics

| Alzheimer's Disease | Dementia | Human-robot Interaction | Older Persons | Robotics | The Observer XT | Video Observation |

Every time I walk in the front door, my dog greets me as if we have been apart for months. On bad or good days, rain or shine, he is always excited to welcome me home. And, let’s face it, even on a lousy day it’s impossible not to smile at the sight of an ear-to-ear doggy smile and a wildly wagging tail.

Pets are good for us; they provide companionship and unconditional love. They can even offer health benefits such as lowering blood pressure and heart rate, reducing the stress hormone cortisol, and boosting levels of the feel-good hormone serotonin.

How can robotic pets help out?

Pets often forge a special connection with people with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. It is not uncommon to watch someone change over from emotionless to joyful when a pet enters the room, especially if it triggers pleasant memories.

However, a pet does not always fit in a health care setting. Allergic reactions, pet illness, or fears of a pet are problems that can occur. However, this does not apply to a robotic pet.

Behavioral and psychological problems affect most individuals with dementia at some point during the progression of the disorder. For example, individuals with dementia possibly suffer from depression or anxiety. These behaviors are often difficult for care staff to manage and may ultimately result in increased medication use and decreased quality of life. Researchers have sought to investigate how robotic pets can be used to control such behaviors.

Cuddling a pet reduces stress and depression

The therapeutic seal robot PARO was launched in Japan in 1993 and elicits emotional responses in the older people, thus giving a calming effect. The cuddle robot has the same effect that a pet can offer, namely, reducing stress and depression. The big advantage of robotic animals as opposed to real pets is that they do not have to be taken care of. The "owner" does not have to feed or walk the pet.

The seal robot is equipped with tactile sensors that react to touch, sound, and movement. It shows autonomous behavior: it can move its tail and flippers, open and close its eyes, and make sounds similar to a real baby harp seal. Its soft pelt is also very appealing.

The largest study ever done on robotic pets

Researcher Wendy Moyle, who has had several family members suffer from dementia, is driven to improve the quality of life for people with dementia. She and her team set up a cluster randomized controlled trial to explore if the use of a robotic seal as a therapeutic tool would influence the emotional and behavioral symptoms of dementia. They compared sessions with PARO to sessions with a look-a-like plush toy and usual care.

More than 400 people with documented diagnoses of dementia living in 28 long-term care facilities in Australia participated.

Participants allocated to the PARO intervention group received an individual 15-minute session with PARO three times a week for 10 weeks. The research assistant left the participant alone with PARO to interact with it as he or she liked -- for example cuddling it, making eye contact, or talking to it.

Participants allocated to the plush toy intervention group received the same sessions as described above, but were given a plush toy (PARO with robotic features disabled). Participants in facilities assigned to usual care received standard care.

Measuring the outcomes using video observation

The three primary outcomes of interest were changes in participants’ levels of engagement, mood states, and agitation after 10 weeks of the intervention. Video observation of participants was used to measure these changes. All video data were coded with The Observer XT using the Video Coding Protocol-Incorporating Observed Emotion Scheme.

Facility care staff completed the 14-item Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory-Short Form (CMAISF) at baseline, week 10, and week 15, rating on a 5-point scale the frequency that participants displayed agitated behaviors during the previous 2-week period.

People with dementia benefit from a robotic pet

What the researchers hoped for was found to be true. The PARO group was significantly more verbally and visually engaged with the robotic seal than the plush toy group. Participants demonstrated greater verbal communication and eye contact with PARO.

Regarding mood states, both PARO and plush toy groups demonstrated greater reductions in neutral affect than usual care, while PARO was specifically more effective than usual care in improving pleasure. Moreover, PARO demonstrated effectiveness in reducing agitated behavior compared with usual care, although the size of this difference was small.

The researchers stress that PARO should not be used to replace staff time, but rather be used during those inevitable periods when staff are otherwise occupied, or when the individual may benefit from comfort from PARO.

FREE TRIAL: Try The Observer XT yourself!

Request a free trial and see for yourself how easy behavioral research can be!

- Work faster

- Reduce costs

- Get better data

References

- Moyle, W.; Jones, C.J.; Murfield, J.E.; Thalib, L.; Beattie E.R.A.; Shum, D.K.H.; O’Dwyer, S.T.; Mervin, M.C. & Draper, B.M. (2017). Use of a Robotic Seal as a Therapeutic Tool to Improve Dementia Symptoms: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Jamda, 18, 766-773.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3opo3yOZweo&t=49s

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g1WR3jsOpbo

Related Posts

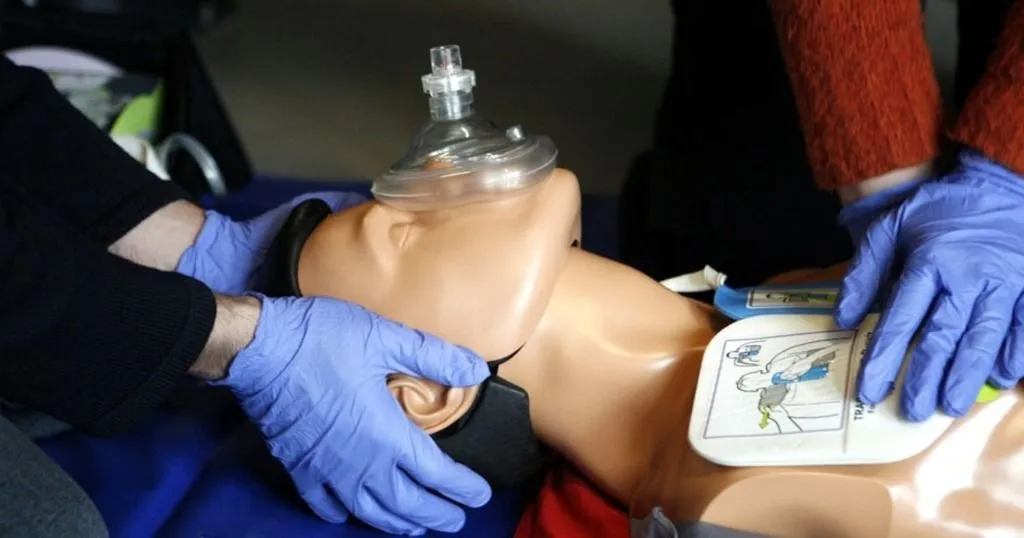

Does the sex of a simulated patient affect CPR?

Implementing Tailored Activity Programs