Anxiety and Autism

The EU-AIMS and AIMS-2-TRIALS projects have carried out some interesting studies teasing out the causes of anxiety in children with autism.

Posted by

Published on

Fri 12 Nov. 2021

Topics

| Anxiety | Autism | Behavioral Research | Developmental Psychology | Emotions | Project |

Autism is a condition which is characterized by difficulties in social communication (e.g. avoiding eye contact), restricted and repetitive behaviors (e.g. body rocking, rituals) and sensory anomalies (e.g. insensitivity to pain or hypersensitivity to noise).

Those characteristics are used in the diagnosis of children with autism. That can be difficult though because they are very variable (it is not called the autistic spectrum for nothing), and also communication difficulties can mask other factors.

Anxiety and autism

In addition to those diagnostic features, autistic children experience other problems, including anxiety, much more than other children. In general, 27% of children experience problems with anxiety, but in children with autism that can be as high as 70%.

What is the relationship between the behaviors typical of autism (communication difficulties and repetitive behaviors) and anxiety? Does one cause the other, and if so which way round? How are they related? It is most likely a bidirectional relationship, with communication problems causing anxiety and anxiety making communication more difficult. But if we can better understand the roots of anxiety in autism, then that might help provide targets for early interventions, which should improve long-term prospects for the children.

Autism Innovative Medicine Studies (AIMS)

Often, by the time a child has an official diagnosis, both autistic behaviors and anxiety are already present, and then it is too late to be able to figure out what is going on. Scientists working in the EU-AIMS project and its successor, the AIMS-2-TRIALS project (both of which Noldus was happy to participate in) figured out a way to solve this problem [1]. Part of that research is what is described in this blog.

Autism has a genetic component - it tends to run in families. That means that if a child has an autism diagnosis, there is a 20% chance of their younger brother or sister also having autism. That compares with about 2% of the general population. Those children were followed from before their birth, and in that way it was possible to see in detail how they developed and tease out how various factors relate to each other.

Fear of the unknown

Behavioral inhibition is a term for heightened fearfulness, shyness and wariness towards novel stimuli. If presented with something new, infants with behavioral inhibition are likely to be a bit afraid of it. That can lead to them avoiding new things and unfamiliar people. That in turn can mean that they will be less socially competent and less assertive. In the end, that can lead to problems with anxiety.

That is so in the general population, and this study [1] showed that it was also the case for autistic children. Autistic children with increased behavioral anxiety at 24 months showed increased anxiety at 36 months.

Emotional control

When children get to about one year of age, they begin to develop emotional control. That means that they can regulate their emotions appropriately in response to what is going on around them. That is also called effortful control. If children do not develop the ability to be able to do that, it can lead to behavioral inhibition and then anxiety (as well as other problems).

This study showed that you can also see that the other way round. If the child can learn regulatory control, then this can protect them against developing anxiety later. That means that interventions which help a child develop self-control in late infancy could help, and that the timing of those interventions is probably important.

The final conclusion from the study is that one reason that anxiety tends to occur in autistic children is because their autism means that they have less effortful (or regulatory) control. That means that they are less able to compensate for other background risk factors, that is, risk factors which occur to a varying extent in the general population.

Limitations

Those conclusions are interesting and can potentially lead to valuable interventions to reduce anxiety in the children when they get older. However, it is worth noting that all the information about anxiety and other problems were reported by the parents. There are a number of potential problems with that, which might lead to inaccuracies or biases in the data.

The children studied all have an older brother or sister with a diagnosis of autism. That might affect the judgement of the parents of the younger child. It might also mean that the parents themselves are more anxious or that they shield their children from novel situations and people, which could itself result in behavioral inhibition and anxiety in the children studied.

Objective measures

Those sorts of limitations are inevitable in studies which rely on subjective opinions of people. In order to go a step further, it is necessary to find objective ways of measuring the behavior of the people being studied. That methodology is also being developed in the AIMS-2-TRIALS project.

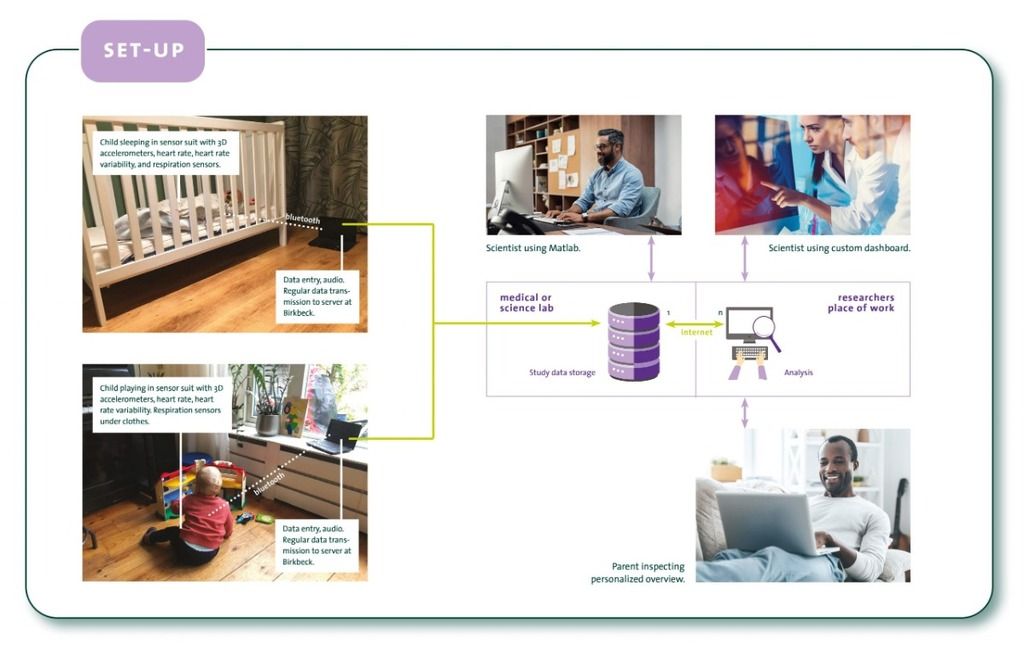

In partnership with the academics in the project, Noldus and DEMCON are developing a smart baby suit. This will enable the researchers to objectively measure the movements and physiology of the baby in his or her home environment. The physiology gives insights into stress and other relevant mental states. The information is complementary to the subjective input from the parents and avoids the stress and disturbance of bringing the baby into the lab for studies.

Reference

[1] Ersoy, M., Charman, T., Jones, E. J. H., & Team, BASIS. (2020). Developmental Paths to Anxiety in an Autism-Enriched Infant Cohort: The Role of Temperamental Reactivity and Regulation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04734-7

Acknowledgements

The work described here was funded by a variety of sources, including the EU's Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) EU-AIMS (grant No. 115300) and AIMS-2-TRIALS (grant No.777394) projects. For details of the other grants, see the Funding section of the above paper.

The illustration is taken from the AIMS-2-TRIALS website.

Related Posts

Exploring the early development of referential gestural communication

Facial mimicry and social cognition in children with autism spectrum disorder