(Un)social rats: the role of dopamine and the amygdala in social adversity

With optogenetics and behavioral testing, researchers found a link between infant social adversity and decreased social behavior in the circuitry of the amygdala.

Posted by

Published on

Thu 08 Sep. 2022

(Un)social rats: the role of dopamine and the amygdala in social adversity

Many psychiatric and developmental conditions, including autism, anxiety, and depression, often have a common denominator: disrupted social behavior. Though researching the influence of the brain on behavior is not easy, scientists from various institutes in the USA and Canada have come up with an interesting approach [1]. They used viruses and optogenetics in an attempt to link certain brain circuits to social deficits.

Badly-functioning neural circuits are known to be capable of causing social interaction deficits, often occurring in psychiatric conditions. Technical limitations so far made it difficult to study those circuits, so not much is known yet about their development, be it typical or pathological.

Amygdala and dopamine in development

The researchers in this current study used the TH-Cre rat model (useful for studying neurodegenerative conditions), and wild type rats as a control. The main focus was on specific parts of the amygdala, which has a primary role in emotional responses, and is used in the current study to investigate social behavior during infancy.

This specific age group was studied with the goal to investigate the role of the amygdala, and the dopamine networking therein, to uncover the emergence of social deficits during early-life which show a lifelong propagation.

Circuitry in the Amygdala

Adversity in the rat pups was introduced through procedures with the caregiver. Deciding if social stimuli are a threat (adverse) or not is done through the basolateral amygdala (BLA), which receives most of its dopamine from the ventral tegmental area (VTA). Together, they form the VTA-BLA circuit. Too much dopamine, and the threat/safety evaluation is impaired.

Early trauma in infants, associated with the caregiver, can have severe effects on this system. Adapting an optical circuit dissection technique made it possible in this study to investigate this neural system in these very young pups.

Treatments during pup developmentAdversity through parenting

For the experiment, infant Long-Evans rats are used. Their date of birth is counted as PN0, and they were reared normally until PN8 and again after PN12, while half of the rat litters were assigned to scarcity-adversity rearing, where cage bedding was reduced to 1.2 cm (control litters had a typical layer of 5-7 cm bedding material) from PN8 to PN12. See the full materials and methods used in this study in the paper by Opendak et al [1].

Reduced bedding material caused rough handling of the pups by the mother and an inability to build a proper nest, while maintaining normal weight gain. The goal of this treatment was to cause social adversity at an early age.

Shock procedures

At PN12, the pups were split into 3 groups; “shock alone”, “shock with mom” and “control”. Each pup was put into a transparent container alone, or with their respective ‘mom’, which either was or was not anesthetized. A non-shock, no mother group served as a control. It did not matter for the outcome whether the mom was conscious during this shock procedure or not.

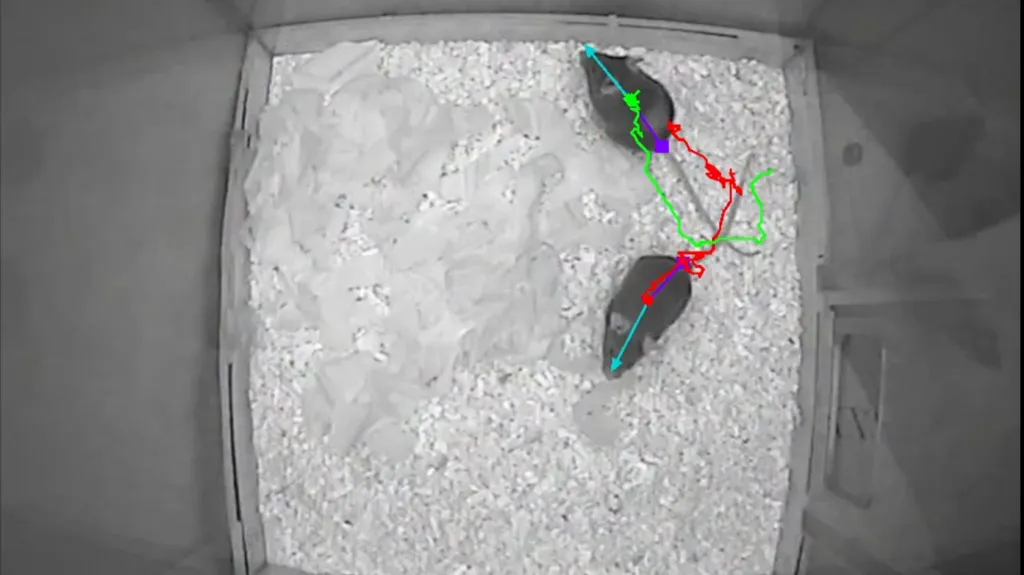

This procedure was repeated over 5 days, in which, among other, the pups’ ultrasonic vocalizations, limb movement per shock (4 limbs + head) were recorded, and behavioral activation was measured using Noldus’ EthoVision XT. Infant ultrasonic vocalizations are a measure of pup distress, and serve an important communicative role in eliciting caregiving behaviors.

Ultrasonic vocalizations and atypical maternal (social) behavior

Initially the researchers in this current study found that on the first day of shock procedures, pups with their mom present (whether anesthetized or not) emitted fewer ultrasonic vocalizations than shocked pups that were alone. This difference however dissipated as the 5-day testing procedure continued.

No difference in ultrasonic vocalizations was found in the adversity-reared pups compared to control, nor were there significant atypical behaviors found towards the mother in this groups (such as sleeping behind the mother’s back or failing to approach the dam and nurse). This effect was however clearly distinguishable in the pups that were shocked with their mom present.

Description of the social interaction tests

The pups underwent a mom-pup social interaction test on PN13. For 30 minutes, the pups were together with the anesthetized mom, and several behaviors were scored: time nipple-attached, time at mother’s ventrum (not nursing), going behind mother’s back, and stereotyped behaviors.

A different group of rats (weaned at PN21) was tested at 22 ± 1 days old, in a 3-chamber social test apparatus. After 5-min acclimation, a littermate and a novel peer were put into two small, perforated metal boxes, one in each of the outside chambers. The test animal then had 10 minutes to explore. Using Noldus EthoVision XT, duration of nose contact with the other rats, time spent in each chamber and activity level were recorded and analyzed automatically.

Surgery treatments

Next to various brain analyses (see the original paper), the pups had two surgeries, one for optogenetic manipulations, the other for microdialisys, in order to prepare them for the social behavior tests. Microdialysis at PN13 (after probe implantation in the BLA at PN10-11) showed that shock with the mother was associated with a specific increase in dopamine efflux. Adapting these procedures for these young pups showed that there was engagement of the amygdala which was causal in decreasing social approach towards the mother (and towards novel peers).

Optogenetics

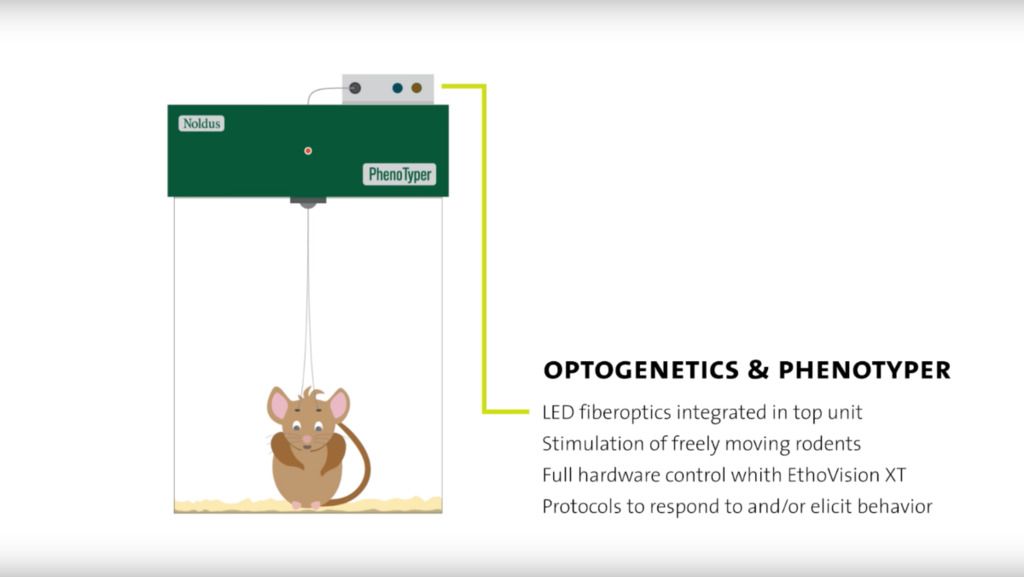

The surgery to prepare the optogenetic manipulation took place at PN1, where each rat received a dose of a tailored virus into their amygdala. Both the TH-Cre pups and the wild type pups each received one of three viruses, so six viruses in total. The viruses were either a control, or contained genes that are capable of either suppressing (Arch) or enhancing (ChR2) amygdala activity.

Each virus contained a “light switch”, which could be used to activate the genes once a laser beam was aimed at them. During PN8-12 the shock procedures and behavioral assessment (as described above) took place, and on PN13, each rat received an optical fiber implant into the BLA.

After recovery, the pups underwent social testing (PN14-15) with their ‘mom’. This showed that the previously described decreased approach towards the mother after the shock procedures, could be rescued by inhibition of the BLA with 532 nm light. Using Noldus’ EthoVision XT, the behavior between “on” and “off” bouts was analyzed automatically and compared.

Conclusion

This study revealed that VTA-BLA brain circuit is indeed causal when it comes to decreased social behavior both toward the mom and their peers. The circuit will become hyper-engaged in social adversity experienced during infancy, but not in adversity experienced alone. It might therefore be a good new therapeutic target for the social interaction deficits that are rooted in psychiatric disorders. If this adversity is repeated, the caregiver of the rat infants has a decreasing ability of regulating the neurobehavioral response to threat, i.e. calming their young.

Reference- Opendak, M., Raineki, C., Perry, R. E., Rincón-Cortés, M., Song, S. C., Zanca, R. M., ... & Sullivan, R. M. (2021). Bidirectional control of infant rat social behavior via dopaminergic innervation of the basolateral amygdala. Neuron, 109(24), 4018-4035.

- Opendak, M., Raineki, C., Perry, R. E., Rincón-Cortés, M., Song, S. C., Zanca, R. M., ... & Sullivan, R. M. (2021). Bidirectional control of infant rat social behavior via dopaminergic innervation of the basolateral amygdala. Neuron, 109(24), 4018-4035.

Related Posts

Horses: behavioral research, physiology and biomechanics

Behavioral Tests in the Dark: Will Researchers See the Light?