Agricultural pesticides and Parkinson's Disease: current screening procedures

Parkinson's disease, what are its symptoms? What role do environmental toxins play in its development? And why should we be critical on current toxin research methods?

Posted by

Published on

Wed 17 Jan. 2024

Topics

| Parkinson's Disease | PhenoTyper | Toxicity |

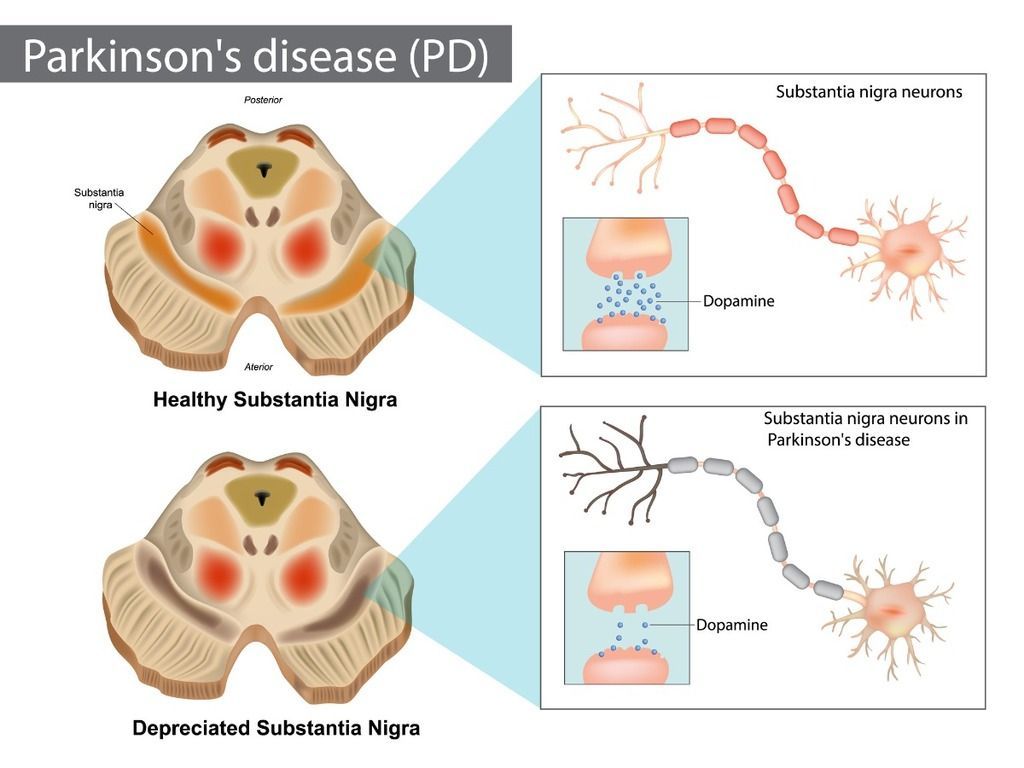

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most prevalent neurodegenerative diseases in the world, increasing significantly over recent decades. PD is characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (Latin for "black substance"), a critical structure in the midbrain region which plays a vital role in movement control. Its dark appearance (and hence the name) is due to high levels of neuromelanin in the dopaminergic neurons.

Although PD is primarily recognized as a movement disorder, it also encompasses several non-motor symptoms.

Key Parkinson’s Disease symptoms in humans and rodents

Motor symptoms Humans | Motor symptoms Rodents | Non-Motor symptoms Humans | Non-Motor symptoms Rodents |

Tremor: often a resting tremor, noticeable in the hands, arms, or legs when relaxed. | Tremor-like movements: Although not as prominent as in humans, some models show tremor-like activity. | Cognitive changes: issues with memory, planning, or decision making. | Cognitive impairments: memory and learning deficits are evaluated using mazes and other cognitive tests.

|

Bradykinesia: slowness of movement, a hallmark of PD, making daily activities difficult and time-consuming. | Reduced movement and slowness: Analogous to human bradykinesia. | Sleep disturbances: insomnia, restless leg syndrome, and REM sleep behavior disorder. | Sleep disturbances: altered sleep patterns observed in some models.

|

Rigidity: stiffness in the limbs or torso. | Rigidity and postural instability: assessed through various behavioral tests.

| Mood disorders: depression and anxiety. | Mood alterations: changes in behavior indicative of depression or anxiety. |

Postural instability: issues with balance and coordination, leading to a higher risk of falls. | Impaired coordination and balance: evaluated using tests like the rotarod or beam-walking assays. | Gastrointestinal issues: such as constipation. | Gastrointestinal dysfunction: such as changes in bowel movement regularity. |

|

| Sensory symptoms: altered sense of smell and pain |

|

|

| Autonomic dysfunction: changes in blood pressure, sweating and bladder control. |

|

Modeling Parkinson's Disease in rodents

To study PD, researchers often turn to rodent models, primarily in mice and rats. These models provide a valuable tool for understanding the disease mechanisms and testing for potential treatments. These models replicate many key aspects of human PD, including both motor and non-motor symptoms, though with some limitations in fully replicating the human condition.

By observing and quantifying changes in rodents’ behavior and neurological function, these can be used as proxies for human symptoms. For example, in assessing motor coordination and balance, a rat or mouse might be placed on a rotating rod (rotarod test) to measure its ability to maintain balance, mirroring the motor coordination issues seen in PD patients.

Creating rodent models of Parkinson's Disease

Rodent models of PD are typically created using neurotoxins like 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), MPTP, or rotenone, which selectively destroy dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. Genetic models, which replicate mutations found in familial forms of PD, are also used.

A recent review by Shan et al. compared the toxins rotenone and paraquat, which induce PD-like features in mice, and provide a broader perspective, as they are commonly used pesticides, thus linking PD research to real-world environmental concerns.

Agricultural pesticides, a serious (mental) health threat

Shan et al.’s review aims to substantiate the relationship between exposure to environmental toxins and the risk of developing Parkinson's disease (PD). The authors highlight the inadequacy of current screening procedures to assess specific PD risks associated with exposure to toxins, particularly pesticides, solvents, and heavy metals such as lead, mercury, arsenic, cadmium, and chromium, which can be found in the environment, products we use, and even in our food and water.

They therefore suggest a detailed and enhanced approach to toxin screening, involving multiple stages, as a crucial step in generating useful information. This data can then guide policymakers and governments in identifying environmental factors that may contribute to the risk of Parkinson's disease.

Multi-tiered screening process

Shan et al. propose a multi-tiered screening process, starting with in silico studies and followed by in vitro tests, whole-organism models, and in-depth rodent models. This approach which aims to identify neurotoxic compounds and understand their mechanisms, creates a more robust approach to better understand the effects these environmental toxins can have, and perhaps offer a pathway to more effective PD prevention strategies.

Measuring behavior in Parkinson's disease (PD) rodent models

The use of rodents in testing for the effects of neurotoxic compounds on the onset of Parkinson’s disease is crucial. Furthermore, rodent models also give key insights into the progression of the disease. Behavioral changes in rodents serve as indicators of neurodegenerative processes and are used to evaluate the efficacy of the multi-tier screening approach reviewed by Shan et al. The following tests can be used to research these behavioral endpoints.

Methods of measuring behavior- Behavioral test battery: This includes a series of tests such as the open field test for exploratory behavior, rotarod test for motor coordination, Catwalk XT test for gross motor function, pellet grasping test for fine motor function, grip test for muscle strength, and apomorphine-induced rotation test for detecting dopaminergic circling deficits.

- Automated home cage monitoring: Tools like Noldus’ PhenoTyper are used to assess day/night activity patterns and anxiety levels in rodents. This includes tests like the light spot test for anxiety and cognition wall for measuring reversal learning.

- Neurochemical assessments: In addition to behavioral tests, some of the animals need to be sacrificed at different time points to assess dopamine neuron degradation in the substantia nigra, which is critical for understanding the neurochemical changes underlying the observed behaviors.

In the context of PD research, behavioral measurement is crucial, especially in the latter stages of toxin screening involving rodent models. Such behavioral data are essential for understanding the neurotoxic impacts of these compounds and their potential link to PD.

A comprehensive approach to Parkinson’s disease

The work by Shan et al. represents important steps in the understanding of PD. Taking a critical look at the pesticides we use in agriculture, and what effect they can have on our health long term, is crucial for our long-term health. Many debates exist, and have long existed, about the use of pesticides, and we must remain critical.

Clear screening and testing procedures for its health effects, short and long term, are crucial to collect the evidence we need to fully understand these effects. Which is why the review by Shan et al. is important to take note of.

Linking pathology to behavior still remains a crucial last step in validating disease models such as described here. Using tools like the PhenoTyper and CatWalk XT, researchers can make these leaps, and validate on symptom level, that we are indeed modelling a human analogue, and work accordingly towards treating these symptoms, maybe even the disease itself.

Reference

Shan, L.; Heusinkveld, H.J.; Paul, K.C.; Hughes; Darweesh, S.K.L.; Bloem, B.R. & Homberg, J.R. Towards improved screening of toxins for Parkinson’s risk. npj Parkinsons Dis. 9, 169 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-023-00615-9

Related Posts

Alzheimer's: prevent instead of cure?

Part 2: How researchers use the Morris water maze to find treatments for AD