Student facial expression analysis while watching instructional videos

Is boredom the opposite of interest? Lídia Vinczéné Fekete and her research team used FaceReader and The Observer XT to find out what makes students get bored and which elements encourage interest.

Posted by

Published on

Mon 06 May. 2024

Topics

| Behavioral Psychology | Education | Emotions | FaceReader | Facial Expression Analysis | The Observer XT |

This blog post was written by Lídia Vinczéné Fekete, Education Methodology Advisor at the Centre for Educational Quality Enhancement and Methodology of the Corvinus University of Budapest.

Student facial analysis while watching instructional videos: Is boredom the opposite of interest?

Boredom, a common challenge among higher education students, has been extensively studied in recent years (Finkielsztein, 2020; Sharp et al., 2020; Yadegaridehkordi et al., 2019). Studies have shown its significant negative impact on student performance and well-being. While boredom involves reduced attention and task involvement, it's more than just a lack of interest. (Pekrun et al., 2023; Westgate & Wilson, 2018).

With help of the results of such studies, educators can develop instructional materials more effectively by understanding the factors that influence student engagement. A recent study (Sass et al., 2023) explores the dynamic between boredom and interest in student facial expressions during instructional video watching, shedding light on their interplay.

Methods to measure students’ emotional state

The study measured students' emotional states using different tools and channels:

- Their facial expressions while watching the video were analysed with FaceReader

- Before and after watching the video, they completed a questionnaire assessing their emotional state

- Finally, they shared their experiences and opinion about the video in the frame of interviews

Results of the questionnaires and automated facial expression detection were analysed by SPSS, FaceReader, and The Observer XT. The instructional video was 22.4 minutes long, so, with the help of The Observer XT, the videos of each participant (recorded by FaceReader) were divided into 30-second time windows.

FREE WHITE PAPER: FaceReader methodology

Download the free FaceReader methodology note to learn more about facial expression analysis theory.

- How FaceReader works

- More about the calibration

- Insight in quality of analysis & output

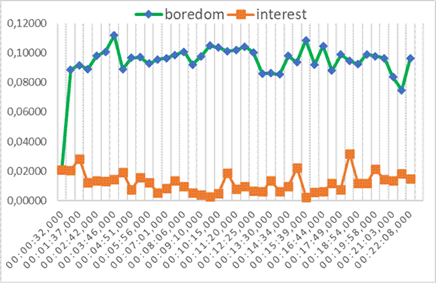

Boredom and interest were measured with the help of the custom expression analysis function of FaceReader. With The Observer XT the mean values for boredom, interest, arousal, and valence for these intervals (see the graph below) were calculated.

Figure 1: Changes in the mean values of boredom and interest per 30 seconds while viewing a 22-minute long video presentation (N=25), measured by facial expression analysis, in 30-second long periods.

What makes students get bored

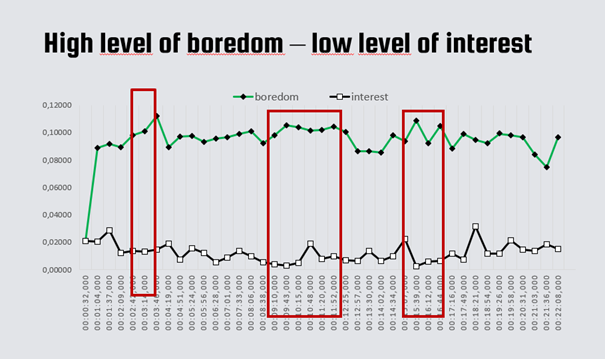

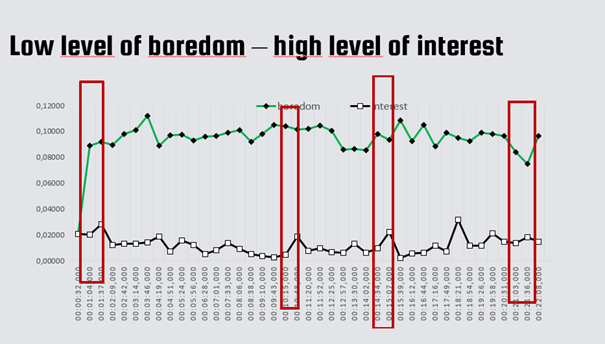

Contrary to the assumption that boredom is solely a lack of interest, results revealed an asynchronous relationship between boredom and interest. Factors such as low arousal levels and a "neutral" state played significant roles in boredom. Surprisingly, low interest did not always correlate with high boredom, and vice versa.

In the analysis of average scores, however, the study identified periods where boredom and interest moved in opposite directions. This raises the question: what occurred in the instructional video during these intervals when boredom increased while interest decreased? In other words, what made students bored?

Figures 2 & 3: What happened in the video when boredom and interest contradict?

Elements that encourage students’ interest

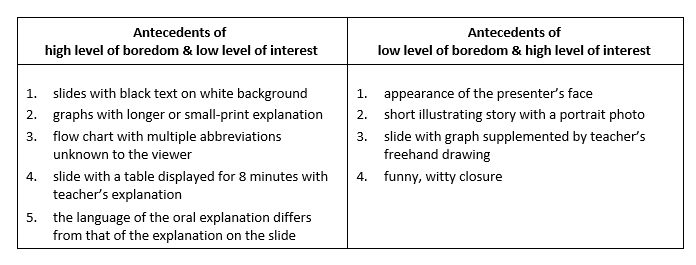

Interviews with students provided additional insights. Visual elements such as graphs and pictures, along with engaging examples and the appearance of the presenter's face, played crucial roles in maintaining attention. Conversely, text-heavy slides and lengthy explanations hindered interest.

Overall, the study underscores the importance of video design principles in promoting student’s continued interest. Multimedia elements, personalization, and minimizing textual overload can enhance learning experiences and mitigate boredom.

By understanding the factors influencing student interest, educators can create more effective instructional materials.

The results of the study are summarized in the table below.

Table 1 – Features of video followed by episodes of viewer boredom and interest

References

- Finkielsztein, M. (2020). Class-related academic boredom among university students: A qualitative research on boredom coping strategies. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(8), 1098–1113. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1658729

- Sass, J., Vinczéné Fekete, L., & Bodnár, É. (2023). Boredom as a Challenge to Knowledge Acquisition: Mapping Boredom-Inducing Elements of a Video Presentation, Using Multimodal Measurements. In Proceedings IFKAD: Managing Knowledge for Sustainability (pp. 2379–2393). https://m2.mtmt.hu/api/publication/34026526

- Sharp, J. G., Sharp, J. C., & Young, E. (2020). Academic boredom, engagement and the achievement of undergraduate students at university: A review and synthesis of relevant literature. Research Papers in Education, 35(2), 144–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2018.1536891

- Yadegaridehkordi, E., Noor, N. F. B. M., Ayub, M. N. B., Affal, H. B., & Hussin, N. B. (2019). Affective computing in education: A systematic review and future research. Computers & Education, 142, 103649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103649

The implementation of the study presented was supported by the UNKP-23- 3-II-CORVINUS-139 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Related Posts

How students can learn through hands-on experience

How to train students in soft skills: Tools and Techniques