Fake or real? AI illusions on the street

In Faux Out-Of-Home (FOOH) advertisement, real-world images are combined with computer-generated imagery and shared on social media. What happens to consumers' perceptions and emotions when you disclose that AI was used?

Posted by

Published on

Thu 22 Aug. 2024

Topics

| Consumer Behavior | FaceReader | FaceReader Online | Facial Expression Analysis | Measure Emotions | Attention |

This blog post was written by Joyce Massop, who completed her Master's degree in Communication Sciences at Radboud University in Nijmegen, The Netherlands. The thesis was supervised by Paul Ketelaar, Assistant Professor in Communication Science and the Behavioural Science Institute (BSI) at Radboud University.

In today's digital society, the use of AI in creating online marketing campaigns plays an increasingly significant role. One example of this is the viral marketing technique called Faux Out-Of-Home (FOOH), where real-world images are combined with computer-generated imagery and spread across social media.

A notable instance is a video of the French fashion brand Jacquemus, which went viral in a matter of seconds with a catchy campaign. The video showed the popular Bambino bags shaped like buses driving through the streets of Paris.

AI use in advertising: new rules

Given this trend, governments are introducing regulations that require the use of disclosures for AI-generated content [1]. An AI disclosure informs consumers about the technological origin of the advertisement and helps them recognize the presence of AI [2,3]. This can take the form of a hashtag or textual mention in a post, such as “Generated by AI.”

Using AI disclosures may give consumers the impression that the campaign creators put less effort into making the advertisement [4]. On the other hand, disclosing AI techniques can lead to a sense of transparency [5], thereby eliciting more positive emotions [6] compared to when there is no disclosure.

Learn more about neuromarketing research.

Understanding AI disclosures in FOOH marketing

The study examined the impact of AI disclosures on the emotional response among young adults. The goal was to understand whether revealing AI-generated content via an AI disclosure affected how young adults emotionally perceive a brand.

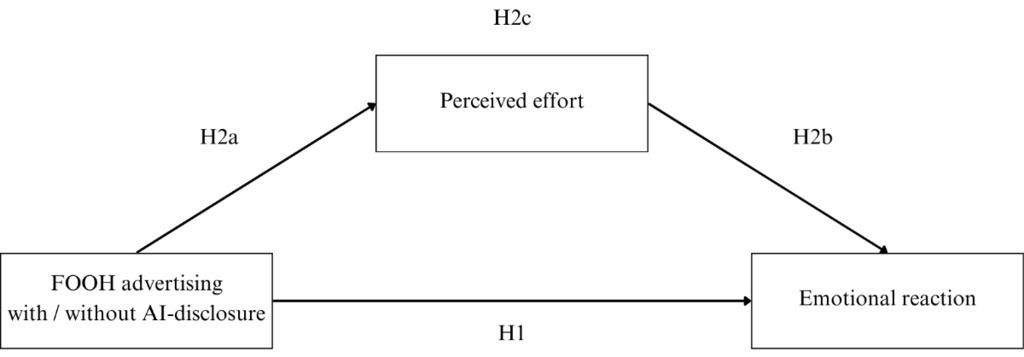

To better comprehend the effect, the study investigated whether perceived effort played a mediating role in this process. Figure 1 shows the research model of this study.

Figure 1: Research model

Measuring emotional response with FaceReader Online

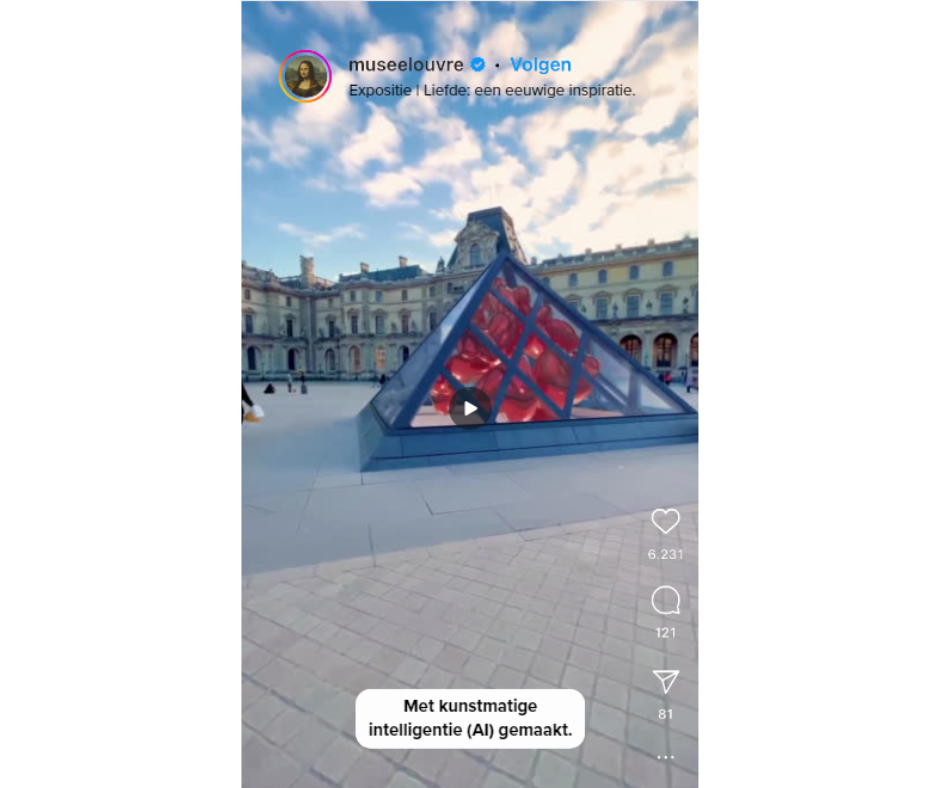

The study was conducted using FaceReader Online among Dutch young adults between the ages of 18 and 29. A total of 110 participants were randomly assigned to two groups. Both groups were shown an Instagram reel (short video) featuring the Louvre in Paris showcasing a Fake Out-Of-Home marketing campaign.

In this video, the pyramids of the Louvre opened up, releasing numerous heart-shaped balloons. Participants in the experimental condition saw a visual AI disclosure in the video, while those in the control group did not see any AI disclosure. The textual AI disclosure read: “Created with Artificial Intelligence (AI)” (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Textual disclosure in the experimental condition

The study utilized a Qualtrics survey seamlessly integrated with FaceReader Online. Combining the Qualtrics survey with FaceReader Online allowed the researcher to measure the emotional response quickly and easily.

Clear instructions were provided to participants during the measurement, resulting in reliable data collection. The recorded data was immediately analyzed and clearly presented with graphs and figures.

No effects of AI disclosure

Interestingly, no noticeable effect of AI disclosure (present/absent) was found on both emotional responses and perceived effort. This suggests that disclosing AI-generated content might not have a direct impact on the emotional responses and perceived effort of young adults.

You may also like this blog post about how to increase attention in commercials for Gen Z.

How FaceReader Online can offer new insights

This study highlights the importance of understanding consumers' emotional responses to AI-generated content, as this can influence their attitude towards the promoted brand. Therefore, future research on consumers' emotional responses to AI disclosures might benefit from using FaceReader Online more frequently.

This study has demonstrated that FaceReader Online is an effective method for measuring subtle and unconscious emotional responses in the context of FOOH marketing. Especially in experimental settings, FaceReader Online can be valuable because even when participants are aware of the camera and try to present neutral reactions, unconscious emotions can still influence brand attitude [7].

RESOURCES: Read more about FaceReader

Find out how FaceReader is used in a wide range of studies and how it can elevate your research!

- Free white papers

- Customer success stories

- Featured blog posts

Uncovering unconscious emotions

FaceReader is a reliable tool for assessing emotions, as traditional methods for measuring emotions, like self-report scales, may not always be considered accurate due to the subjective nature of emotions and personal interpretations. Moreover, cognitive processes triggered by advertisements often operate at an unconscious level, making it difficult for consumers to be aware of them.

Additionally, emotions have often been measured with self-report scales in previous research, but this method is not always seen as accurate due to the subjective nature of emotions and individual interpretations [8,9]. Moreover, cognitive processes activated by advertisements often occur unconsciously, making it hard for consumers to be aware of them [10,11]. FaceReader Online offers significant potential in this regard, as it is a valuable tool to enhance our understanding of emotions and, more specifically, to effectively measure the impact within the context of FOOH marketing.

FaceReader Online is a valuable addition in this respect and can complement scientific knowledge in the context of efficiently measuring emotions and, more specifically, AI disclosures in FOOH marketing.

Also read: Why you should use FaceReader Online for your human behavior research.

Facilitating large-scale emotion research

Lastly, FaceReader Online is user-friendly and allows for the recruitment of a large number of participants. Integrating FaceReader with online surveys makes research easy to distribute. Participation is convenient for respondents, as they can choose if and when they want to take part in the study. This facilitates large-scale research.

By utilizing FaceReader Online, we can improve our understanding of emotions, supplement existing scientific knowledge and measurement methods, and gain valuable insights into the effects of emotional responses.

References

- Auteursbond. (2023, 16 oktober). AI en auteursrecht. Auteursbond. https://auteursbond.nl/ai-en-auteursrecht/

- Evans, N. J., Phua, J., Lim, J., & Jun, H. (2017). Disclosing Instagram Influencer Advertising: The Effects of Disclosure Language on Advertising Recognition, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intent. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 17(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2017.1366885

- Boerman, S. C., Van Reijmersdal, E. A., & Neijens, P. (2012). Sponsorship Disclosure: Effects of Duration on Persuasion Knowledge and Brand Responses. Journal of Communication, 62(6), 1047–1064. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01677.x

- Rhee, H., & Lee, K. (2024) Generative AI disclosure in fashion marketing: A tectonic shift in the advertising landscape, ITAA Proceedings, Conference: Bridging the Divide, Baltimore Maryland, 1-3. DOI: 10.31274/itaa.17359.

- Wojdynski, B. W., Evans, N. R., & Hoy, M. G. (2018). Measuring Sponsorship Transparency in the Age of Native Advertising. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 52(1), 115–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12144

- Beckert, J., Koch, T., Viererbl, B., & Schulz-Knappe, C. (2021). The disclosure paradox: how persuasion knowledge mediates disclosure effects in sponsored media content. International Journal of Advertising, 40(7), 1160–1186. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1859171

- Hudders, L., De Jans, S., & De Veirman, M. (2020). The commercialization of social media stars: a literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. International Journal of Advertising, 40(3), 327–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1836925

- Barrett, L. F. (2017). How Emotions are made. The secret life of the brain. Revue québécoise de psychologie, 40(1), 153-157. https://doi.org/10.7202/1064926ar

- Suhr, Y. T. (2017). FaceReader, a Promising Instrument for Measuring Face Emotion Expression? A Comparison to Facial Electromyography and Self-Reports (Master’s thesis). Accessed from https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/352187

- Bagozzi, R. P., Gopinath, M., & Nyer, P. U. (1999). The Role of Emotions in Marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(2), 184–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070399272005

- Mizerski, R., & White, D. J. (1986). Understanding and using emotions in advertising. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 3(4), 57-69. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb008180

Related Posts

Package testing - Emotional journey in packaging research

How innovative solutions advance your behavioral research